“Groundhog Day” featuring the great Bill Murray is considered to be a cult classic. Released in 1993 the film grossed $70,907,146 worldwide. When it was rereleased in 2021 it made an additional $200,989 worldwide. In addition to being a box office success and cult classic many consider it to be a vehicle for examining core Buddhist concepts, such as rebirth, karma and Samsara. Since its release the film has nestled itself firmly in the American Zeitgeist, even (ironically) being streamed on repeat on Television networks like AMC all day long on Groundhog day. One could make the argument that it’s one of the most popular pieces of Buddhist media in Americana, outside of the presence of practicing Buddhist Lisa Simpson.

The Plot of Groundhog Day: Bill Murray’s Time Loop Journey

Bill Murray plays Phil Connors, a curmudgeonly news reporter assigned to cover Groundhog Day in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania. Phil feels unfulfilled covering the event for the fourth year in a row alongside his new producer, Rita Hanson, and cameraman, Larry. A rapidly approaching blizzard adds an additional feeling of dread to his already sulky attitude. Phil gives an apathetic report on the event then tries to high-tail it out of town, only to be stopped by the blizzard and forced to spend another night in the “hick” town. The next morning Phil wakes to the same song, Sonny & Cher‘s “I Got You Babe“, on his radio alarm clock. He chalks it up as a moment of Deja Vu. To his horror, Phil comes to the realization that he’s trapped in a time loop. Forced to relive the same day again, and again, and again, indefinitely. Phil becomes increasingly desperate to leave this cycle of one-day Samsara, eventually even trying to commit suicide, only to wake up to the same song on the radio day after day. As the film progresses we watch Phil struggle to come to terms with his new reality.

Living in the Moment Mindfully… No Matter How Many Times You Do It

In the film Connors falls into a deep depression. The character feels that because there’s no future there’s no point to life. We see him start to develop nihilistic tendencies and he begins to use the town’s people as an outlet for the ennui he’s feeling. He regularly manipulates situations for his own benefit, regardless of the negative impact it has on the people around him.

At some point Connors inadvertently discovers the power of mindfulness. He learns to live in each moment and find joy. It dawns on him that each moment is different and can yield a different outcome. He performs the Heimlich maneuver on a choking Diner patron, changes a tire for a stranded driver, and catches a child who falls from a tree. He knows there’s no long term benefit to his actions. The choking patron will be alive and well the next day, the stranded driver will still be inconvenienced tomorrow, and the boy falling from the tree is doomed to the same painful fate day after day. Connors is fully present in each moment and takes Right Action, without getting caught up in worries about the future or regrets about the past that do not exist from his perspective. He’s able to find happiness and escape the feeling of tedium by being present in each moment.

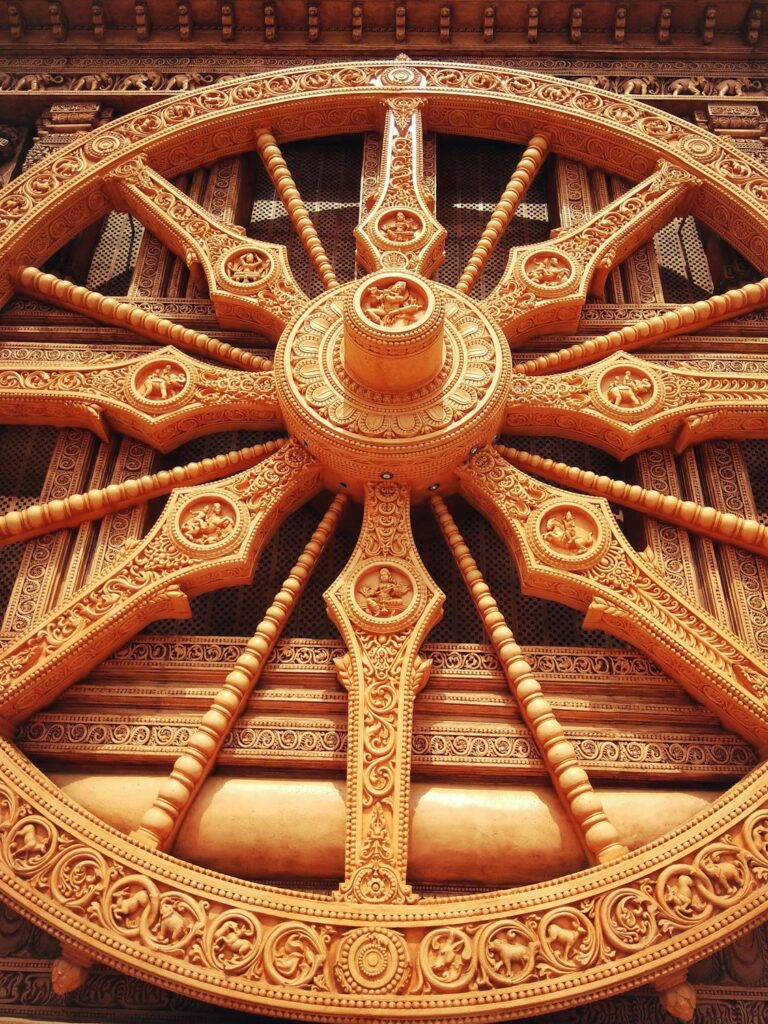

Small Scale Samsara: Phil Connors and the Wheel of Life

Samsara is the endless cycle of life, death and rebirth. Samsara is often characterized as suffering or Dukka and is represented as “The Wheel of Life“. To Phil Connors there is no greater suffering than being forced to relive the same day over and over again in what he describes as a “hick town”. Saṃsāra means “wandering” when translated from Devanagari and is sometimes also translated as “cycle of life” when translated from Sanskrit. Samsara is a complex subject and interpretation varies based on what sect of Buddhism you’re referencing. For the purposes of this film “wandering” may be the best definition. Phil feels unfulfilled for a majority of the film, wandering through every day. Feeling like his actions have no impact and no destination. Phil feels there is no cause and effect in his day to day life. He thinks he cannot accrue Good Karma. As a result he makes no effort. He unwittingly dooms himself to never escaping the cycle. Connors is stuck in an endless cycle of waking, going to bed and waking again in the same circumstances. Without knowing it, he traps himself in this level of reincarnation. Never progressing out of his current realm of existence. This is a very high-level, generalized view of Samsara but may be one of the most obvious examples of Buddhist teachings in the movie. His day to day life is a metaphor for the lifetime of actions for a normal person.

Rebirth: Phil Doesn’t Escape the Mini Samsara Cycle Until He Builds Good Karma

In the beginning of the film Connors uses his day-long infinite loop purely for selfish reasons. Binge eating with no fear of long-term health effects. Engaging in thrilling high-speed car chases with local police knowing he’ll wake up the next morning in the comfort of his Bed and Breakfast. Using information gained in previous loops to seduce women into one night stands. The cycle continues on and on.

Connors doesn’t escape the cycle until he uses his situation to bring joy and happiness to those around him. In the third act of the film his new producer, Rita Hanson, unknowingly convinces Connors to view the loop as a gift rather than a curse. From that moment on, Connors uses the loop to cultivate good karma. He uses his knowledge to help the local townspeople. Delivers a genuine and passionate report on the daily activities that brings the celebration to a halt as all those within earshot stop to appreciate his delivery. Most importantly, after giving a heartfelt piano rendition of of Rachmaninov’s “Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini” Connors expresses his feelings of true love, not lust, for his producer, Hanson.

Throughout the third act we see Connors unknowingly align himself with the Buddhist precepts;

- Refrain from taking life

- Refrain from taking what is not given

- Refrain from the misuse of the senses

- Refrain from wrong speech

- Refrain from intoxicants that cloud the mind

He stops having callous disregard for the town’s people’s lives and makes many unsuccessful attempts to save a homeless man’s life. Rather than stealing for his own gain he gives to those around him. He stops trying to pass the time using drugs and alcohol and develops skills, such as piano playing, that bring joy to others. Finally, he stops lusting after Hanson and develops true feelings of love. It’s only after this personal growth that Phil goes to bed with Hanson and wakes up to a new morning show on his radio alarm clock for the date of Feburary 3rd. Signaling that he has escaped the endless loop of Groundhog Day.

Harold Ramis and His “Buddish” Beliefs

Harold Ramis, director of Groundhog day, has gone on record saying the film was never meant to be a Buddhist film. In fact, he’s stated the movie was a reflection of his own personal beliefs, which he describes as “Buddish”. Despite not being a full fledged Buddhist, Ramis is no stranger to Buddhist teachings. During an interview with Lion’s Roar contributor, Perry Garfinkel, Ramis rattled off the Four Nobel truths and admitted to wearing Mala beads around his wrist in the past. In spite of his own spirituality, Ramis said he was surprised the film struck a spiritual nerve with so many viewers. While the script never explicitly uses the words “Buddhism” or “Buddhist” Ramis says the comedy of the film was influenced by Buddhist beliefs.

“The primary rule of Buddhist humor is that you never laugh at someone else’s expense. But, rather, laughter arises when we realize our futile attempts to escape the first noble truth. Pointing to our common bumbling deluded nature—with humor—apparently relieves some of the suffering. Ramis has done that in most of his films, but especially in Groundhog Day, where he seems to be saying, ‘This is what it’s like. Every day is the same thing; we make the same mistakes over and over.’ Ramis is always trying to shatter our ordinary take on reality, to reveal hidden dimensions. He is trying to create what Buddhists would call ‘beginner’s mind.’”

Perry Garfinkel

You won’t hear a character chanting mantras, you won’t hear Phil Connors recite the Nobel Eightfold Path, and you won’t see any characters wearing Kāṣāya throughout the film. Yet the seeds of Buddhism can be found if you look deeply into the film. The film ends with Connors acting much like a bodhisattva navigating through the cycle of Samsara. Performing acts of kindness not for his own personal gain like in the beginning of the film, but for the sake of doing acts of kindness, even if they’re impermanent and erased by the next morning when he awakes to the familiar sound of Sonny and Cher blaring from his radio alarm clock.